The $10 Million Comedy Company With No Address

Secret comedy shows are selling out barbershops, scuba stores, and auto repair shops across America. No formal advertising. No venue overhead.

80 people packed into a scuba shop on the Upper East Side to watch five comedians they had never heard of. Tickets cost $55. There was no sign on the door. Every seat was full.

This scene is no longer unusual. A new wave of pop-up comedy producers are selling out shows in unconventional, non-traditional venues, from barbershops to auto repair shops to candy stores, dismantling the friction of the traditional comedy club model that rely on two-drink minimums, and a reliance on specific entertainment districts to survive.

The movement has scaled rapidly.

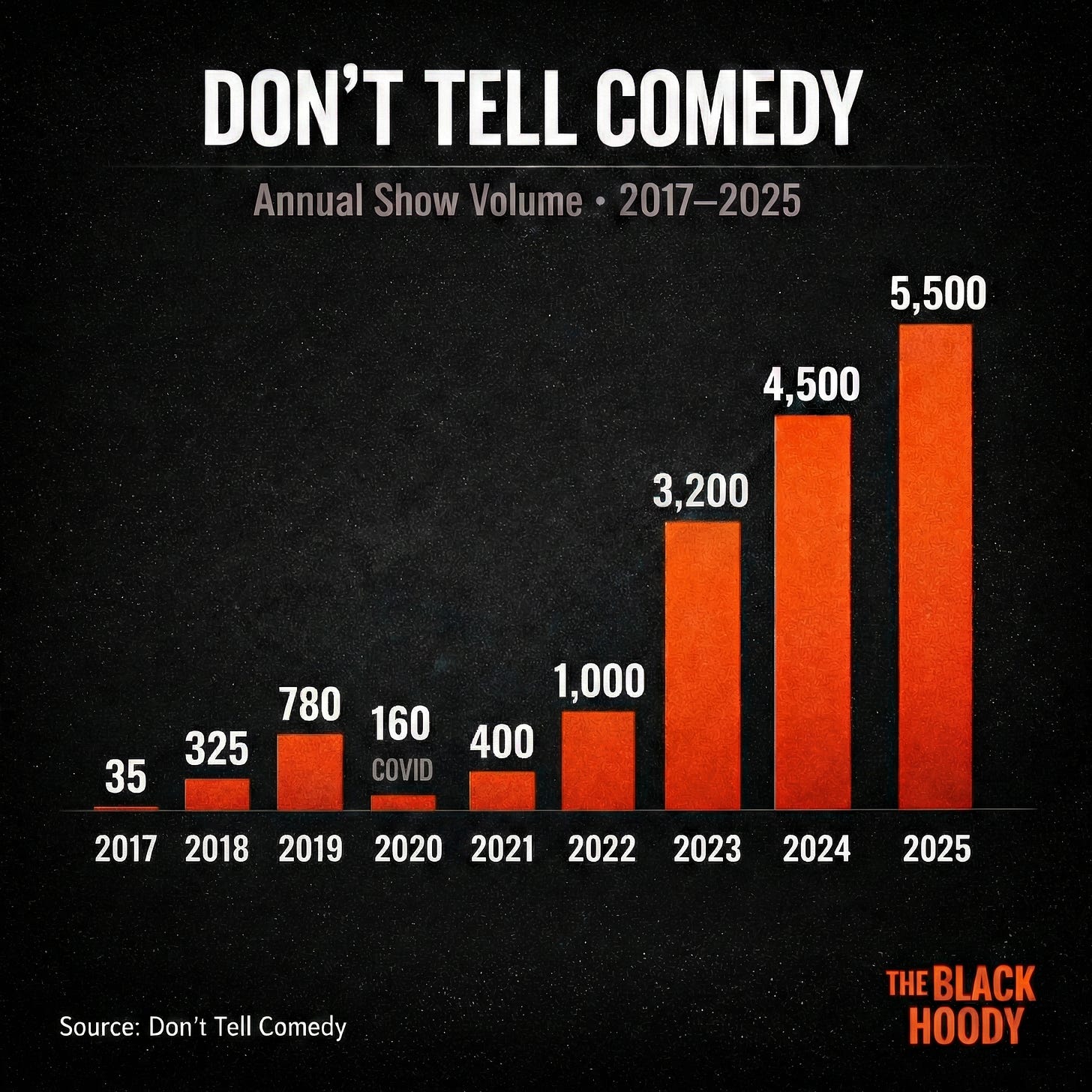

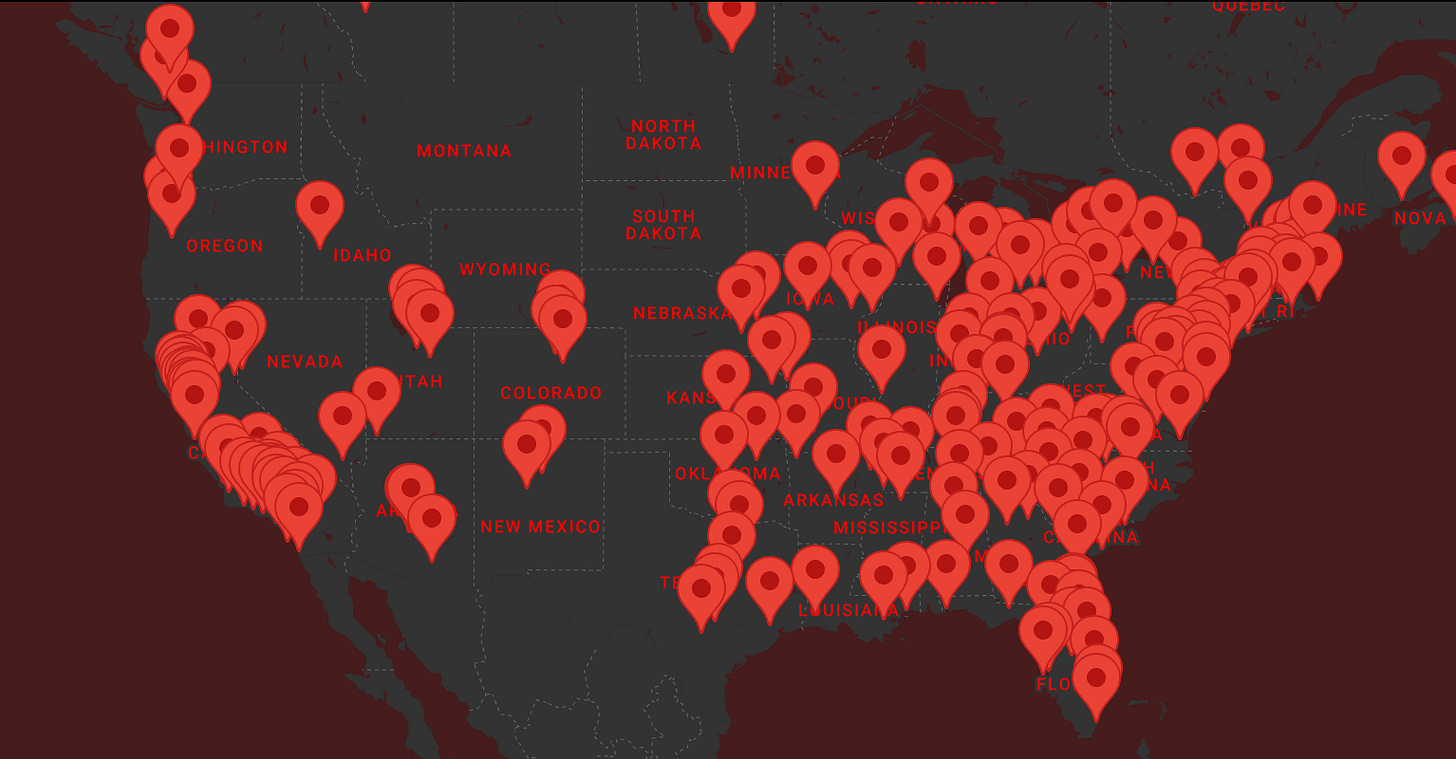

Don’t Tell Comedy, a pop-up stand-up company founded in 2017, has grown from roughly 35 shows in its first year to 5,500 shows in 2025, operating in over 250 cities globally. Comedy Underground Overground (Comedy UO), founded in New York in 2021, has produced more than 330 shows across 85 venues, built a waitlist of 35,000 people, and recently signed with WME.

Both companies have done it with minimal traditional advertising, relying instead on word of mouth, social media, and the simple appeal of watching live comedy in a place you are not supposed to be.

Together, they represent two distinct models of pop-up comedy, one scaling wide, the other going deep, and both are generating growing revenues while expanding the audience for live comedy in ways traditional clubs have not.

The Don’t Tell Model: Scale Across 250 Cities

Don’t Tell Comedy founder Kyle Kazanjian-Amory started the company after growing frustrated with the costs of traditional venues. “Stand-up felt inaccessible,” Kazanjian-Amory told The Black Hoody. “It was expensive, there were two-drink minimums, and you had to go to very specific neighbourhoods. I wanted it to feel like a fun night out, not a transaction.”

Don’t Tell Comedy founder Kyle Kazanjian-Amory

The first show was in a coworker’s friend’s backyard in Silver Lake, Los Angeles.

Thirty-five people attended. Sam Jay, who went on to write for SNL and record HBO specials, performed.

From there, Kazanjian-Amory burned through his savings and eventually liquidated his retirement account to fund the expansion.

It paid off. Don’t Tell’s growth trajectory tells the story:

How the Business Works

Unlike traditional comedy clubs, Don’t Tell generates no revenue from food-and-beverage minimums.

Revenue comes from three sources:

Ticketed live shows

Digital content distribution

Brand partnerships

Tickets typically range from $20 to $40 depending on the event type and market, with an average show size of 55 to 60 people.

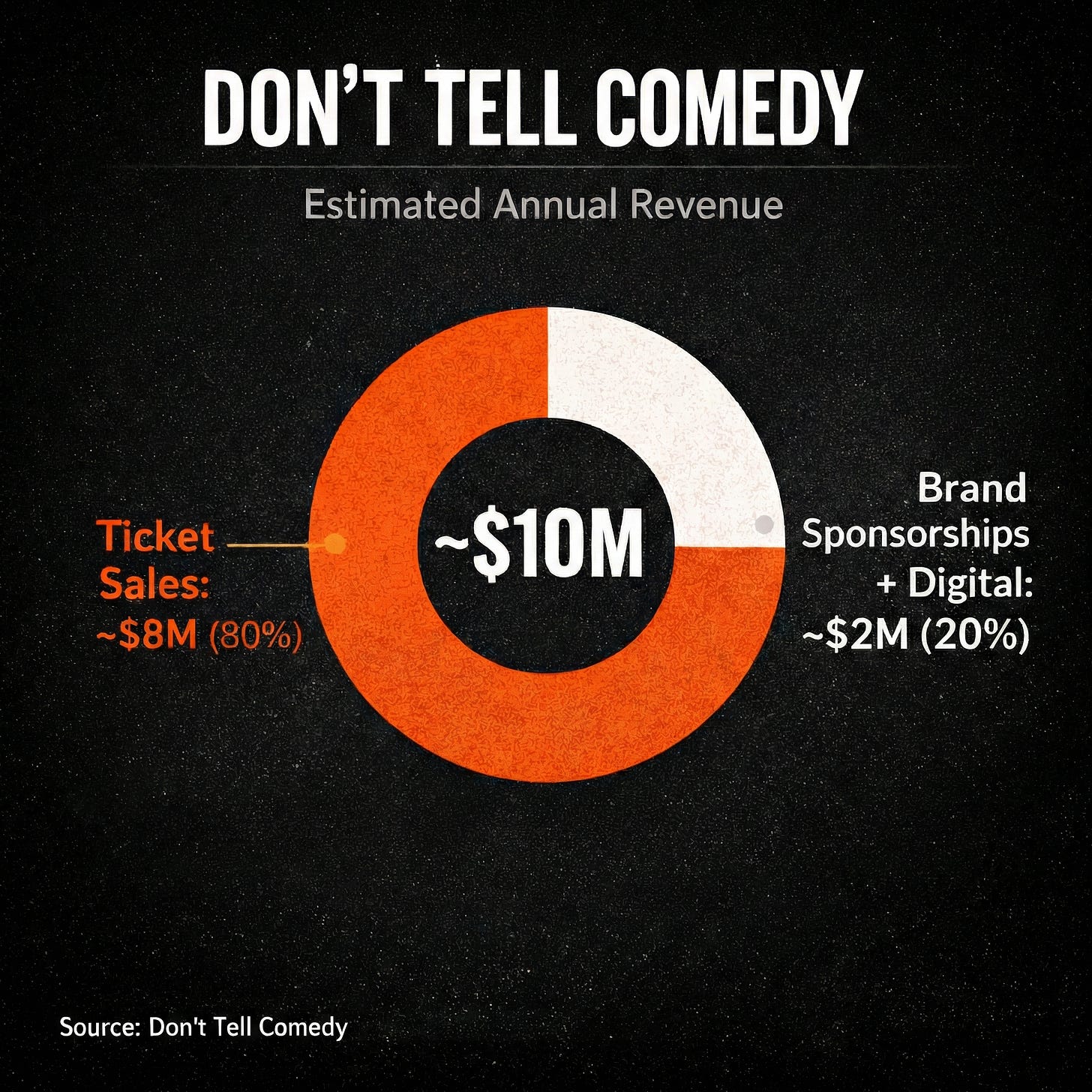

Combined, the company generates approximately $10 million in estimated annual revenue: $8 million from ticket sales across its thousands of shows, plus approximately $2 million from brand sponsorships and digital content revenue.

Note that Don’t Tell Comedy didn’t disclose this $2mil number, this our back of the envelope maths based on their CPMs from their online views + average sponsorship rate on their show volume.

Dr. Squatch serves as the presenting sponsor for all digital stand-up content, and national campaigns.

Unit Economics: Inside a Typical Show

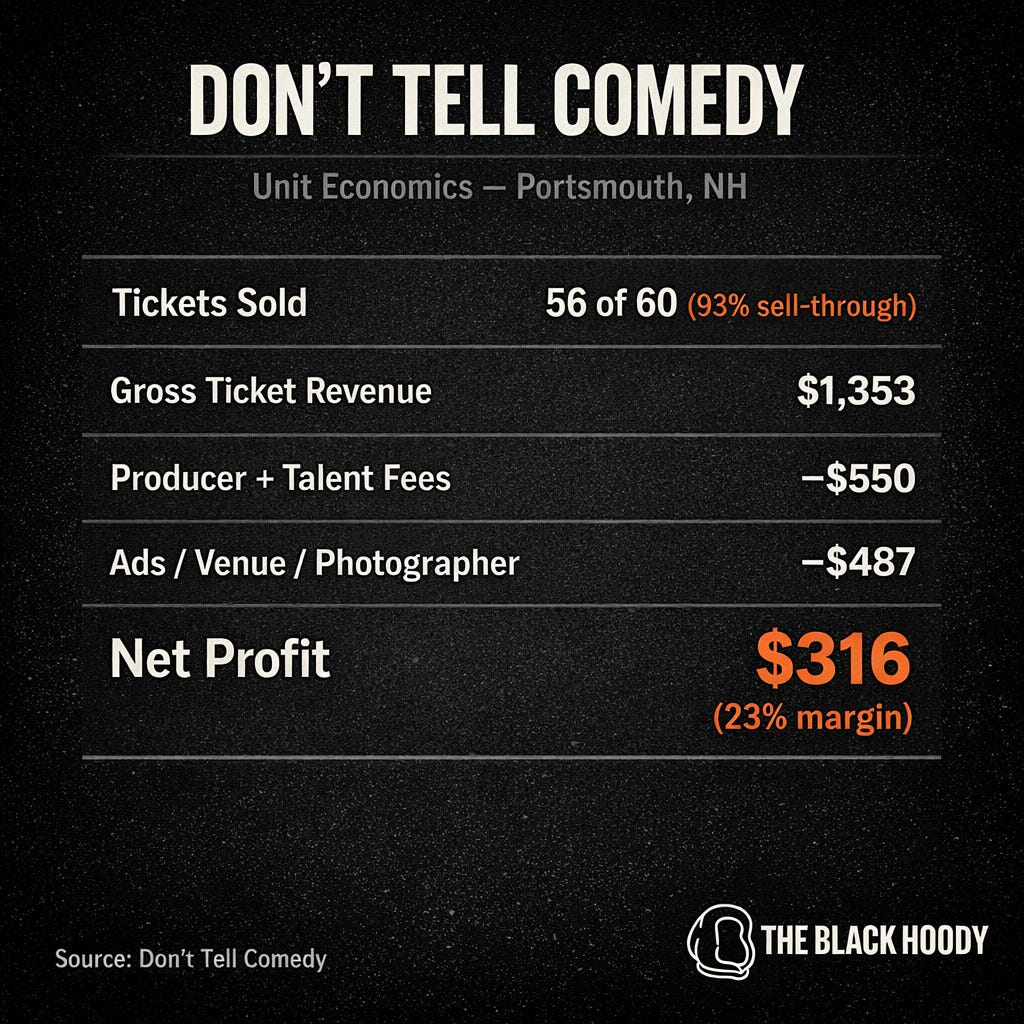

A typical Don’t Tell show in a mid-sized market illustrates how the model works at the individual event level. Take a recent show in Portsmouth, New Hampshire:

Don’t Tell Comedy — Unit Economics (Portsmouth, NH)

A 23% net margin per show is healthy for live events, but the picture is more complex at the corporate level.

Don’t Tell now employs approximately 18 full-time staff, more than half on the live-events side and carries a six-figure annual insurance policy that enables shows in non-traditional venues such as retail stores, boats, and fine art galleries.

More than two full-time employees are dedicated solely to customer service and producer support.

The organisational structure reflects the scale. “After 2022, a real game changer was hiring more people,” Kazanjian-Amory said. “Every city has somebody boots-on-the-ground putting on local shows. We have a head of live events and regional leads, who were some of our best producers that we elevated into those roles. They really get what makes a Don’t Tell show fun and how to keep the standards high as we scale.”

A Night Out, Not Just a Show

The pop-up format solves a problem that has plagued live comedy for decades: friction. Going to a comedy club can feel like going to the movies, you arrive, pay for expensive snacks and drinks, sit in the dark, and leave. The social dimension is an afterthought.

Don’t Tell inverts this. Shows take place in spaces that are inherently interesting, surf shops, recording studios, art galleries, and the experience is designed to feel like a night out with friends rather than a transactional exchange.

“From the get-go, it’s all about the experience,” Kazanjian-Amory said. “If people leave saying, ‘That was awesome, not just a great comedy show, but a super fun night out,’ the word of mouth from that goes a long way. I still believe word of mouth is the best form of marketing.”

That approach also draws a different audience.

“We get a lot of people who haven’t been to a lot of comedy shows,” Kazanjian-Amory said. “That’s why I don’t see us as competitors to comedy clubs. We’re a really great foot in the door, something that’s less intimidating than a club and feels more like a fun night out with friends or a date.”

On average, Don’t Tell audiences skew younger than traditional clubs, primarily the 23-to-35 demographic, though in suburban markets the age range extends into the 40s, 50s, and 60s.

Locations of Don’t Tell Comedy Shows.

The Comedy UO Model: Going Deep in One City

David Levine and Ethan Mansoor, co-founders of Underground Overground Comedy, at Zabars in New York.

If Don’t Tell Comedy is the wide play, hundreds of cities, thousands of shows, a lean producer network, Comedy Underground Overground (Comedy UO) is the deep play: a single-city operation in New York that has turned scarcity and intimacy into its competitive advantage.

Founded in April 2021 by David Levine and Ethan Mansoor, childhood friends who met on the chess team at elementary school on the Upper East Side, Comedy UO started almost by accident.

Mansoor met a comedian performing in a hotel lobby during COVID and asked how to book them for a friend’s rooftop. When agents wouldn’t return their calls, Levine improvised.

“I started lying, saying I booked all their friends in the past. I told Sam Morrill’s agent I booked Mark Normand. I told Mark Normand’s agent I booked Sam Morrill. Somehow we got both of them. Thankfully, they’re at different agencies.”

— David Levine, Comedy Underground Overground

Four and a half years later, Comedy UO has produced shows at more than 85 different venues, laundromats, candy stores, scuba diving shops, thrift stores, and iconic New York institutions including Katz’s Deli, Zabars, Economy Candy, Peter Luger’s, and Russ & Daughters.

Comedians who have performed include Bill Burr, Leslie Jones, Eric Andre, Marcelo Hernandez, and Mateo Lane.

Comedy UO’s New York Focus

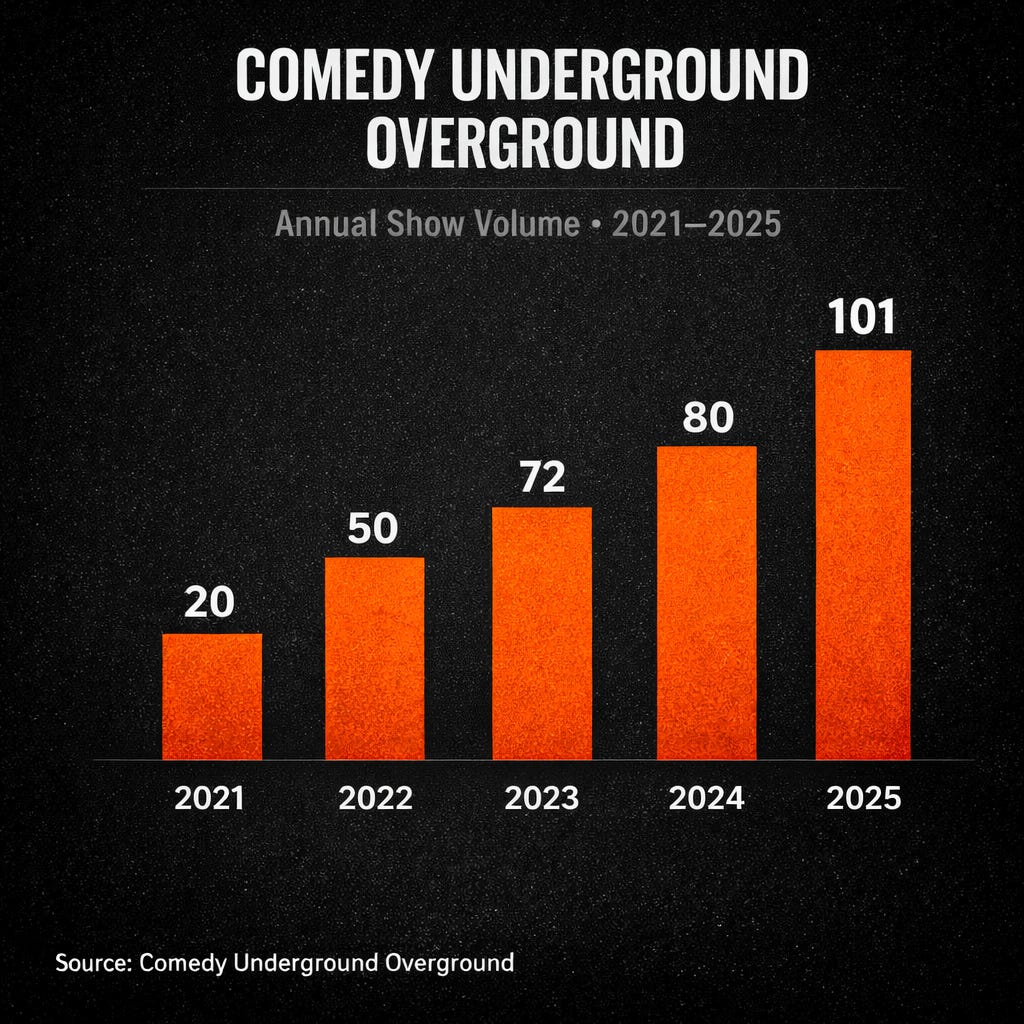

Comedy UO’s growth has been slower than Don’t Tell’s, but the trajectory is steep:

Comedy UO — Annual Show Volume

But the show count only tells part of the story. Comedy UO’s revenue growth has been explosive, with the company reporting the following year-over-year increases:

Comedy UO — Year-Over-Year Revenue Growth

The pattern is telling. Explosive early growth in 2021–2023 as the post-COVID appetite for live experiences surged.

A normalisation in 2023–2024 as that novelty wore off. Then a near-doubling in 2024–2025 as tapings and private events kicked in as a second growth engine.

The Waitlist as a Business Model

Comedy UO does not advertise. Not in the traditional sense, and not even in the Facebook-and-Instagram-ads sense that Don’t Tell employs. Instead, demand is driven almost entirely through Instagram and a waitlist system where Levine personally sends direct messages for ticket drops.

“You sign up for the waitlist and then we get to you chronologically. I’ve sent probably 400,000 DMs. We have about 35,000 people on our waitlist.”

— David Levine, Comedy Underground Overground

For the first three years, almost all tickets were sold exclusively through Instagram DMs. More recently, the company has paired that personal outreach with Shopify-based ticket drops to allow for scale. For larger events like the Big Small Business Tour, Comedy UO uses a sneaker-drop model: “We’ll announce the tour, hype it up, and then tickets will all drop Monday at 7:00 PM,” Levine said. “Everyone on the waitlist gets an email blast saying, ‘Here’s the link.’”

The results speak for themselves. All eight dates of Comedy UO’s Big Small Business Tour from January 12–16 across New York City sold out in advance. A separate show at Margaritaville Times Square also sold out. Tickets range from $40 to $75 for standard shows, with some premium events exceeding $150 per person.

It is worth distinguishing between the two companies’ approaches to audience acquisition. Don’t Tell actively advertises through Facebook and Instagram ads and email marketing, Kazanjian-Amory acknowledges that paid social is one of their primary sales channels. Comedy UO’s genuine zero-advertising model, built on DMs and word of mouth, is rarer and arguably harder to replicate.

The Hospitality Play

Where Don’t Tell positions itself as a scalable live-events platform, Comedy UO increasingly frames itself as a hospitality business that uses comedy as its vehicle.

“People don’t see comedy as a social event. They see it as sit down, go to a show, shut up and leave. What we like to pitch is this is an event. We’re in the events business. When you walk in, you talk, socialise for 30 minutes, we can get you food, drinks, whatever you want. The show is tight, 70 minutes, shorter than your standard show. And then there’s an afterparty where you can hang out more. We can have musicians, magicians walking around.”

— David Levine, Comedy Underground Overground

The pricing reflects this positioning. Comedy UO’s higher ticket prices, often double or triple a standard Don’t Tell ticket, are offset by no drink minimums, included food and beverages at some events, and a curated atmosphere that justifies the premium.

“Those logistical demands can make the business expensive to run. The standard costs are the venue, the comedians, staffing, and the cost of production. Our weekly shows are very labour-intensive. It’s expensive. It is not easy.”

— David Levine, Comedy Underground Overground

Levine estimates that 10–20% of Comedy UO’s audience are experiencing live comedy for the first time, people who discovered the shows through social media and had never set foot in a comedy club.

The crowd skews heavily local: New Yorkers who live in the city full-time, not tourists. “That’s been a big, very attractive thing to a tourist-heavy business,” Levine said.

The Digital Flywheel

Both companies discovered that filming their shows created something more powerful than marketing material, it created an entirely separate business.

Don’t Tell Comedy saw its inflection point in 2022 when it began filming and distributing high-quality stand-up sets online. The company now has over one million followers on Instagram and 2.3 million subscribers on YouTube, plus a substantial presence on TikTok where clips regularly go viral. Some top-performing videos reach millions of views on YouTube.

“We’re putting out two new 10-minute sets on YouTube every week, and a new short-form clip across our social channels every day. That’s still growing and performing really well, and it creates a lot of value for the comics whose sets we tape.”

— Kyle Kazanjian-Amory, Don’t Tell Comedy

“Our intention with digital marketing was we wanted to showcase emerging talent and bring more people to live shows. We didn’t realize it could become a business on its own.”

— Kyle Kazanjian-Amory, Don’t Tell Comedy

The strategy has filled the gap left by Comedy Central’s retreat from short-form stand-up content. “There’s a gap now that Comedy Central isn’t really doing what it used to,” Kazanjian-Amory said. “A lot of people are self-distributing, but what makes our stuff special is that we’re doing it at a really high quality. We’re trying to shoot Netflix-level sets. I think that’s been part of the secret to our success.”

Don’t Tell’s online content has become as well known as, if not more than, its live events, even as live shows still generate the bulk of revenue. Don’t Tell has also licensed content to Hulu and other distributors, and produced Hannah Berner’s Netflix special as a production company.

Comedy UO has followed a similar path, though at an earlier stage. The company now tapes short sets, signing licensing contracts with comedians and distributing clips across Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube, where some videos have reached 150,000 views.

“What these tapings are is we sign licensing contracts with the comedians, we pay them for their set and we do 10-minute tapes. We do five comics on a show, tape their sets, and then we clip it up on our Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok and collaborate with them. And that’s been a huge way to boost the account as well as get ad deals on that side of the business too.”

— David Levine, Comedy Underground Overground

“With digital, it’s unlimited,” Levine said, contrasting the scalable economics of content against the labour-intensive reality of producing physical shows.

Pop-Up Comedy vs Comedy Clubs

Both Kazanjian-Amory and Levine are careful to position their companies as complementary to, not competitive with, traditional comedy clubs. Kazanjian-Amory frames Don’t Tell as a gateway that introduces new audiences to live comedy who may then seek out clubs.

Levine differentiates Comedy UO as a hospitality business rather than a comedy business.

The data supports this. When 10–20% of Comedy UO’s audience has never been to a live comedy show before, that is genuine market expansion, new customers being created for the entire industry, not just for one company. These are people who were not previously spending money on live comedy at all.

That said, the growth of pop-up comedy does surface questions about the economics of live comedy that club owners are already grappling with.

Pop-ups operate with almost no fixed overhead. There is no permanent lease, no year-round staff, no liquor licence. Don’t Tell’s producers source venues on a show-by-show basis, paying only when there is a confirmed event.

Comedy UO negotiates individually with each venue, often bringing foot traffic that the business would not otherwise have. This asset-light model allows both companies to experiment in markets where a permanent club would never be financially viable, and that is arguably good for the industry as a whole, because it grows the overall audience for live comedy in cities that currently have no comedy infrastructure.

The drink minimum is another area where the pop-up model has surfaced a consumer preference worth paying attention to.

For decades, comedy clubs subsidised performer pay and kept ticket prices lower by requiring patrons to spend $15–$25 on drinks. Pop-up audiences have shown a willingness to pay higher upfront ticket prices, up to $75, in exchange for eliminating that friction. Whether this represents a generational shift in how audiences prefer to pay for live entertainment is an open question, but it is a data point that every live comedy operator should be watching.

In our recent conversation with Comedy Cellar owner Noam Dworman, he stressed the importance of keeping his prices low, at $25 per head maximum despite turning away 20k people per week.

WATCH: Comedy Cellar owner Noam Dworman

The logistics of pop-up comedy, however, illustrate why the club model endures. Every pop-up show requires bespoke arrangements for sound, lighting, power, seating layout, temperature control, and insurance. “A warm room is death for comedy,” Levine said. “The room cannot be above 68 degrees when you have 80 people in there.” These operational challenges create a natural ceiling on quality control as both companies scale, a problem that a well-run club with purpose-built infrastructure simply does not have.

The Black Hoody went deep into what it takes to build a great comedy club with Emilio Savonne, the owner of the NY Comedy Club.

WATCH: New York Comedy owner Emilio Savone

The most likely outcome is not that pop-ups replace clubs, but that the two models coexist and push each other to improve. Pop-ups are proving that comedy audiences are larger and more diverse than the industry assumed and maybe acting as a top of funnel for the traditional clubs.

What’s Next

Both companies are expanding beyond standard stand-up, and both are being taken increasingly seriously by traditional industry infrastructure.

Comedy UO signed with WME in 2025, a signal that the agency world sees pop-up comedy as a legitimate and scalable business. The company is expanding into magic shows, “2026 will be the year of magic,” Levine said, partly because magic carries lower perceived risk for corporate clients who worry about the unpredictability of stand-up. Private events, where profit margins are higher, are scaling to Boston, Philadelphia, and Chicago.

Don’t Tell is pursuing a different kind of vertical integration: building a platform that supports comedians across their entire careers. “We’re trying to figure out how we can continue to provide value to comedians across their whole career from doing their first Don’t Tell show, to their first taped set, to maybe a half-hour special,” Kazanjian-Amory said. “We’ve already shot a Netflix special as a production company. So the question now is: what’s the next level after that?”

Internationally, Don’t Tell has tested shows in London, Manchester, Paris, and Barcelona, all English-language for now, and sees significant room to grow before needing to explore other languages. Comedy UO’s ambitions are more localised: Levine’s stated dream venue is the Empire State Building.

The Bigger Picture

Pop-up comedy is the proof case. Two companies, one scaling wide across 250+ cities with a lean producer network, the other going deep in one city with a 35,000-person waitlist and $75 tickets, have independently arrived at the same conclusion: there is a new market for live comedy outside the comedy club.

A note from Luke Girgis

This is the first original guest post on The Black Hoody, and I want to thank Paul for the contribution, and Kyle and David for their transparency in their interviews. It is inspiring to see such success in both of their businesses.

I will be back in Los Angeles and New York next week filming more podcasts for our show. If you have any guest suggestions, please reply in the comments. Both the Comedy Cellar and Barry Katz episodes came from reader suggestions.

Also, for a bit of fun, we have partnered with American Apparel to make Black Hoodies. If you are a subscriber to this newsletter you can get one for free, so stand by for the announcement and check out the design below.